The Black Sea Meeting

On behalf of the Marmara Group Foundation, Mr. Şamil Ayrım, Dr. Fatih Saraçoğlu, Prof. Dr. Mustafa Aydın and Ambassador Koray Ertaş participated in the meeting of co- exchanging opinions on the subject of the Black Sea that the Marmara Group Foundation and the New Strategy Center, which is located in Bucharest, collaboratively conducted with a civil society identity.

The New Strategy Center is represented with the H.E. Ambassador Sergiu Celac, H.E. Prof. Dr. Iulian Fota and H.E. Ambassador Dan Dungaciu.

With his civil society view, H.E. Koray Ertaş, the Turkish Ambassador to Romania was also present at the meeting, in which the subjects of collaboration in the Black Sea were handled.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Vulnerabilities and Opportunities in the Black Sea region

Strategic and geopolitical stakes have always been high in the Black Sea region. Regional developments, both positive and negative, continue to affect the vital interests of the countries and peoples situated along the seashore, sending reverberations well beyond its confines. For countries like Turkey and Romania, linked as they are in a Strategic Partnership, it is important to identify correctly the challenges and opportunities that inevitably arise at a time of unprecedented change. The scientific and academic communities in the two countries have a significant part to play in this regard by sharing conceptual and analytical approaches and seeking adequate responses to the increasingly complicated issues we all have to face. This joint paper is intended as a meaningful contribution to the on-going intellectual dialogue designed to further strengthen the excellent bilateral relations between Romania and Turkey.

- Romanian perspective -

Viewed from Bucharest, Turkey has been a major regional actor for centuries and, in the past 25 years, has taken the lead in promoting a constructive, future-oriented agenda for the Black Sea region. Turkey’s political, economic and military capacity entitles it to play such a role also in the future. Recent regional developments have brought home the notion that Turkey is also a significant actor in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern space. In a statement that reflects the feelings of most Romanians, the President of Romania described Turkey as “indispensable ally for regional stability”.

Black Sea region neighbouring countries

1. Historical background

Since ancient and mediaeval times, the Black Sea has been the point of intersection of flourishing civilisations and sometimes-bitter rivalries for political supremacy or control over trade and maritime routes. Modern history brought to the fore such fundamental issues as the preservation of the regional balance of power and freedom of navigation. That was the reason for the Crimean War of 1853-1856, when major European countries joined Turkey to frustrate Russia’s imperial ambitions in the region. The legal status of the Black Sea (Turkish) Straits was eventually settled through the Montreux Convention of 1936, one of the few international inter-war agreements still valid today. Its provisions, while upholding the principle of free navigation and trade, introduced certain restrictions on the tonnage and duration of sojourn for the naval vessels belonging to non-riparian states.

After the World War II and during the Cold War, the Soviet Union and its satellites controlled most of the Black Sea littoral with the exception of Turkey, a NATO member state. That was a period of relative (and uneasy) stability in the context of strategic stalemate. The dissolution of the USSR (1991), the newly acquired independence of the former Soviet republics and the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to NATO (2004) and the European Union (2007) changed the political picture in and around the Black Sea once more.

For almost two decades, it appeared that the Black Sea region was settling into a new pattern of modern development and constructive cooperation in an increasingly secure environment. NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP, 1994) helped the aspiring candidates and post-Soviet independent states alike to downsize and modernize their armed forces, introduce civilian controls over the military and security establishments, and enhance inter-operative capabilities. The European Union followed up with generous offers of assistance for institution building and administrative reform in the complex transition of those countries to market economy and functional democracy with specific financial instruments under the European Neighbourhood Policy and Eastern Partnership. As early as 1992, Turkey came up with the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) initiative, which eventually developed into a full-fledged regional organisation under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter. The EU responded with the Black Sea Synergy project, which was launched in 2008.

2. A change of strategic paradigm

It all started with the Russian-Georgian war of August 2008, which resulted in the de facto incorporation of one-third of Georgia’s sovereign territory into the Russian sphere of military control. The reaction of the Euro-Atlantic community – distracted by the on-going operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and by the onset of the financial-economic crisis – was weak and inconclusive. This, combined with other internal and external factors, may have encouraged Russia to take a more assertive course by resorting to its growing military power as a primary instrument of foreign policy. The next, more ominous step was the ‘hybrid’ penetration and eventual illegal annexation of the Ukrainian province of Crimea, plus active involvement in support of the secessionist enclaves in southeast Ukraine. The significant military participation of a Russian expeditionary force in the Syrian theatre of war and more subtle political and economic demarches in the Western Balkans indicate the existence of a deliberate geostrategic design to assert Russian supremacy in a wider sphere of self-described ‘privileged interests’. All this relies on an unprecedented military build-up, a demonstrated willingness to use force in order to protect its perceived interests, and extensive, purposeful use of propaganda, information warfare and intelligence operations.

No other region is more illustrative of this trend toward changing the status quo – which Russia now deems to be unsatisfactory – than the Black Sea. The rapid transformation of Crimea into a military stronghold, a sort of land-based aircraft carrier or anti-access area denial zone (A2/AD) was accompanied by an unprecedented growth in the numbers and modern capabilities of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Prior to the occupation of Crimea, the Russian Black Sea navy had 26 surface vessels, 2 submarines, 22 fixed-wing aircraft and 37 helicopters. These were outmatched by the naval forces of the NATO countries: Turkey (44 surface ships, 13 submersibles) plus the out-dated and poorly armed navies of Romania (3 frigates, 4 corvettes, 4 missile patrol boats) and Bulgaria (4 frigates, 2 corvettes, 3 missile boats). This is no longer the case. In the meantime, Russia confiscated 70 per cent of the Ukrainian navy and added new capabilities; so that, by the end of 2015, it had 41 surface vessels and 9 submarines in the Black Sea. According to procurement plans, by 2020, the Russian Black Sea fleet will add 20 new missile corvettes and other craft. Also, 74 aircraft and 61 helicopters, plus 2 regiments of surface to air missiles now provide air cover. Land-based and sea-borne Kalibr missiles, which have southern Italy, southern Germany and the whole of Central Europe within range, supplement offensive capabilities. Some of those weapons, including cruise missiles, can be fitted with nuclear warheads.

Map – range Kalibr cruise misile and Iskander ballistic missile

There have been so many surprises of late in the wider Black Sea space that any attempt to fathom what is likely to happen next is a thankless exercise. Still, here are some hypothetical developments, which, though improbable, may yet come to pass, at least in theory. One of them could be serious tension over maritime space resulting from the incorporation of Crimea by Russia. In the absence of formal, legal delimitation of the territorial waters and air space, continental shelf and exclusive economic zones in the Black Sea, Russia has proceeded with unilateral imposition of its claims by force and confiscation of assets. Under international law and accepted practice, the least that may happen is a series of very costly litigations and arbitrage cases.

Map - New exclusive economic zone delimitation in the Black Sea before and after the occupation of Crimea, the Russian vision

It is now obvious that the strategic balance in the Black Sea region has shifted and is likely to become dangerous. Recent developments have shown that the ramifications of this new situation can (and do) spread to wider areas such as the Levant and the Greater Middle East as well as, potentially, to the Balkans. When faced with apparently intractable problems, we are witnessing a temptation to resort to military force as a substitute to rational political dialogue and reasonable accommodation of mutual legitimate interests within the principles, rules and accepted practice of international relations. This is the first and, probably, the most serious vulnerability in terms of regional stability and security.

3. The nature of ‘frozen’ conflicts

The second, and related, vulnerability arises from the so-called ‘frozen’ or protracted conflicts in the Black Sea region. It is not a mere coincidence that all those conflicts are located in the territories of newly independent republics that emerged after the dissolution of the USSR. They include Nogorno-Karabakh (with an inter-state component between Armenia and Azerbaijan), the Georgian provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, now self-proclaimed but unrecognized ‘independent’ states under Russian military control, and Transnistria, a break-away part of the sovereign territory of the Republic of Moldova, where a Russian garrison is unlawfully stationed. The illegally annexed Crimea and the Russia-sponsored separatist enclaves of Donetsk and Lugansk in Ukraine also fit that category.

Map – Frozen conflicts

In all those cases, what is ‘frozen’ today can become easily ‘unfrozen’ tomorrow, quickly degenerating into open military confrontation. Whenever such conflicts occurred, Russia promptly stepped in to stop hostilities for a while without addressing their root causes and typically introducing a ‘temporary’ peace-keeping force which never intended to leave the scene, thus securing a permanent Russian military presence. The experience of the past two decades has confirmed that Russian strategic planners are able to turn those conflicts on and off at will depending on Moscow’s political and military interests at the moment. Whenever similar tensions arise in parts of the Russian Federation, they are dealt with and terminated ruthlessly; they are never ‘frozen’. The perverse effects of such practices are seen in the political and societal weakening of the target states, exacerbation of internal divisions, economic stagnation and aid-dependence that may last for generations.

4. What about opportunities?

The fact that we have to concentrate on redressing the strategic balance and restoring the primacy of the unanimously agreed principles and norms of international law in and around the Black Sea should not obscure the perennial need to keep the channels of communication open and to engage in constructive debates on realistic ways to move things forward both bilaterally and in a multilateral regional format. The positive experience of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Organization and other regional projects and initiatives should not be allowed to wither and die away no matter how unpropitious the political circumstances may be. While standing firm on our common principles and defending our respective legitimate national interests, we in the scientific and expert community have the ability and the duty to be flexible and realistic in our judgment, to be pragmatic and business-like in the solutions we offer for consideration to the decision makers, to be bold in our quest for positive outcomes and humble about our expectations.

As we prepare to face the consequences of a further deterioration in regional and international affairs, we must also be prepared for a possible upturn to the better. Even though the prospect may look dim for the moment, we must never quit thinking about collaborative projects that would benefit our nations and the region as a whole.

Global problems such as mitigating the effects of climate change, access to resources and energy, sustainable growth and secure jobs, environment protection, reliability of the financial system, cross-border infrastructure, elimination of poverty and ignorance, harnessing the promises of modern technology and many others will not simply go away if we busy ourselves with strategic and defence matters exclusively. The same applies to shared global threats such as international terrorism and organized crime, trafficking of drugs and people, illegal migration, pandemics, etc.

For these reasons we divided our final section into two parts: one dealing with security challenges and the other with opportunities for constructive collaboration.

- Recommendations

- Regional and international security. In line with the decisions of the Warsaw NATO Summit 2016, which re-affirmed the importance of the Black Sea region in the Alliance’s overall defence posture in terms of dissuasion and deterrence, it makes sense to consider a set of follow-up steps such as

- To develop a contingency plan for the southern tier of the Alliance’s Eastern Flank in relative symmetry with the northern tier (Baltic), with due regard to the limitations imposed by the Montreux Convention;

- To enhance the capabilities of littoral NATO member states for the protection of their maritime and air space by deploying advanced air and coastal defence systems, possibly also by undertaking joint air patrols with other allied air forces according to the Baltic model;

- To envisage a multilateral framework for joint training and exercises of the naval forces of NATO littoral states;

- To explore the possibility of initiating a NATO-Russia practical dialogue for agreed confidence-building measure and avoidance of naval or air incidents in the Black Sea space that may otherwise lead to unwanted tension or escalation.

- Renewed efforts for constructive regional cooperation.

- To proceed with a thorough examination of the existing formats for regional cooperation (in particular BSEC and EU Black Sea Synergy) with a view to ascertaining which particular areas or sectors can be realistically activated in the current political circumstances;

- To develop new ‘soft security’ instruments at regional level in such areas as border and customs controls, law enforcement, migration, etc.

- To encourage closer cooperation with those littoral states that have partnerships with NATO and/or association agreements with the EU (Georgia, Republic of Moldova, Ukraine);

- To use fully and more actively the potential of the Romania-Turkey Strategic Partnership for the further development of bilateral relations and possible joint action in regional and international affairs.

- Turkish perspective -

Following the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the enlargement of EU and NATO eastwards, stretching out to the Black Sea, the EU moved in 2004 to strengthen its ties with the countries around the Black Sea region under the scope of the Wider European Neighbourhood policy. The approach initiated by EU for enlargement of its relations with the Black Sea countries reached its destination with the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the EU membership in 2007. With this momentous move, the countries that were previously considered as Soviet Union’s backyard became EU member states.

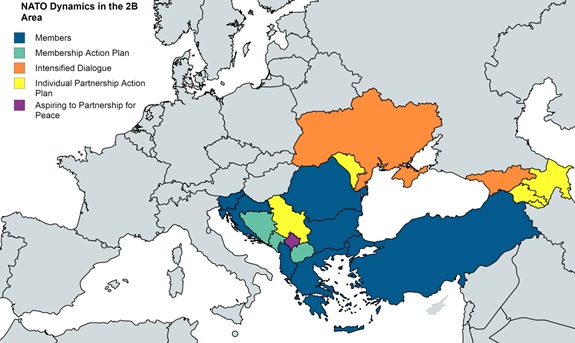

NATO dynamics in the Black Sea and Balkan area

Thus the countries of the Black Sea Region, which was under the Tsarist and Soviet influence for almost two centuries, positioned themselves under the umbrella of western organizations such as NATO and the EU. On the other hand, the primary determinant for Russia in terms of its security and threat conception has been the fear that the disintegration process experienced at the end of the Cold War by the Soviet Union might come back to haunt the Russian Federation. As the ethnic, religious tensions and border conflicts multiplied in the vicinity of Russian borders and showed tendency to affect them, Russia prioritized protection of its borders and unity as a federation by expanding its influence zone beyond its borders to the former Soviet territories. With its “near abroad” policy, Russia effectively declared that it would intervene in the existing conflicts and tensions within its de facto zone of influence that included the Black Sea region as well. Also, the second military doctrine adopted in 2000 considered the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) territory as Russia’s “national security zone” and stated that it would take military action against any perceived threat in this region. The occupation of Crimea by Russia on 27 February 2014 and continuing Russian support to the separatist movements in eastern Ukraine are, in a way, latest manifestations of these earlier declarations and Russian position.

On the other hand, the Black Sea has always been the gateway for Russia to the warm seas. Unlike the other seas around Russia, the Black Sea does not freeze in the winter and thus have continues maritime traffic. Combined with the Dnieper and Dniester river systems, the Black Sea have constituted and important strategic waterway for Russia throughout the history.

For the West, too, the Black Sea is a strategic waterway, allowing access to Russia and helping to contain it. As several cuts in Russian natural gas deliveries to Europe through Ukraine due to political crises between Ukraine and Russia has demonstrated time and again, the Black Sea has also became important in terms of energy security of both regional and European countries. Through several oil and natural gas pipelines around its shores and under it, as well as with tankers travelling across it, the Black Sea has established itself as a secure energy corridor from east to west. As a result, the existence of nearby energy sources has added to the geopolitical significance of the region.

If the Black Sea has emerged as such a security corridor today, it is mostly thanks to the Montreux Convention that ended centuries of rivalry between the great powers of the time for the control of the region, and that regulates the maritime regime of the Turkish Straits (Bosporus and Dardanelles). With the signing of the Convention in 1932, the Black Sea region was excluded from the geopolitical power games. Subsequently, when Soviet Union, with its Warsaw Pact allies Bulgaria and Romania, pressurized Turkey after the end of the Second World War to extend its control over the Straits, Turkey moved to join NATO, thus bringing it into the Black Sea equation as early as 1952. With the inclusion of Bulgaria and Romania into NATO in 2014, further shifted regional security balances in favour of the West in general.

Yet the Montreux Convention also provides security for Russia, too. The Convention provides several limitations for the warships of the non-littoral states in the Black Sea. It limits the length of their stay, allowable tonnage, number of ships, and what they can do and not do while in the region. Yet, Montreux Convention regulates only the maritime passage through the Straits, and by extension in the Black Sea. It does not have anything to do with other dimensions of security, such as expansion of NATO with memberships of for example Georgia and Ukraine, as well as establishment of air and ground bases. This is something that Russia considers as a threat to its existence and thus strives to block the further expansion of NATO into the region. As such, its intervention into Georgia in 2008 and to Ukraine 2014 could be seen from this perspective.

The shifting balances of power in the Black Sea region has resulted in ambiguities for many sub-regions that are already plagued with so-called frozen conflicts. Not only they could be unfrozen at any given moment, as seen in the recent flare up between Azerbaijan and Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh, but also the constant Russian meddling of them and its attempts to use them to create leverages for Russian influence in the region creates further security threats by prolonging instability in the region. Conscious that most of the regional countries would gravitate decisively towards the West if given choice, Russia tries to keep them unstable and unbalanced through manipulation of their weaknesses, especially related to their frozen conflicts.

The 2014 fait accompli in Crimea and continuing Russian support for the separatist in eastern Ukraine expanded frozen conflicts throughout the Black Sea region and added new areas to already existing conflicts over Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistrea. To counter these attempts, the transatlantic community tried to respond with sanctions against Russia, as well as new security measures to be taken within NATO.

On 15 September 2016, a day prior to his arrival to Turkey, the Chief of General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, General Valery Gerasimov, in what could be classified as a non-conventional announcement, declared that the superiority of the Turkish Navy to the Russian Black Sea Fleet was over. Although rather uncommon and un-political to make such a statement before what supposed to be a friendly trip to a neighbouring country, this behaviour and pronouncement needs further elaboration. Indeed, similar statements were also by the General Valery Gerasimov, this time regarding land and air forces in the Caucasus region, following an earlier military exercise carried out in the north Caucasus on 9 September 2016. While they point to the Russian fear of being surrounded by more powerful countries, and obsession to be the dominant country in its neighbourhood, they also indicate to accumulating treat poised by increasing Russian armament and aggressiveness in the Black Sea region to the neighbouring countries.

While the fact that Turkish Navy was able to compete and balanced the Russian Navy in the Black Sea until recently had provided a comforting thought, the current imbalance in expansion of navies and other military spending in the region creates concern for Turkey and other regional countries, as well as NATO members. The changes in Russian behaviour and capabilities, despite its financial difficulties, disrupt region’s natural evolution and challenge the Western engagement in the region.

Yet, the fact remains that the best way forward would be development of multilateral cooperative environments, instead of competitive insecurities. For this, improving Turkish-Romanian bilateral relations and coming with alternative joint regional initiatives might provide just the much-needed opening for the regional security and stability.

New Strategy Center (NSC) is a Romanian think tank, non- governmental organization, designed to provide a debating framework on topics of major interest for Romania. NSC submits relevant topics both in terms of threats to national security, and opportunities for economic development of the country to the general consideration and debate. The Balkans and the Black Sea are the main points of interest for NSC, a large and complementary area with a significant impact on Romanian security. The defense, the connection between the military modernization and industrial development, the energy security, the technological development, the challenges of the hybrid threats, the public diplomacy and the cyber security are some of other issues on which NSC is focused on.

Marmara Group Strategic and Social Research Foundation was established as an independent Non-Governmental Organization in 1985 and organizes meetings, seminars, and conferences, and prepares reports and analyses to offer solutions to problems of Turkey. The Mission of Marmara Group Strategic and Social Research Foundation is to think about and discuss Turkey’s problems such as economy, democracy and security and to share ideas with the public through rational and scientific solutions. In this direction, Marmara Group Strategic and Social Research Foundation conducts researches and implements projects with the Middle Eastern, Balkan, and Eurasian Countries’ national and international think-tanks.

This assessment was coordinated by Ambassador Sergiu Celac on behalf of the Scientific Council of the New Strategy Center, and Dr. Mustafa Aydın on behalf of the Marmara Group Strategic and Social Research Foundation.